History, sovereignty, and contemporary life in the Four Corners region

In the southwest corner of Colorado, where the Colorado Plateau tilts toward Utah and New Mexico and the San Juan Mountains fade into high desert, lies the homeland of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe.

Centred near the community of Towaoc, the Tribe occupies a landscape that has shaped human history for thousands of years – canyons cut by ancient rivers, mesas etched with rock art, and a distinctive mountain whose profile resembles a reclining figure, known locally as the “Sleeping Ute.”

The story of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe is not confined to the past. It is a living narrative of sovereignty, adaptation, and endurance. It encompasses deep Indigenous histories, colonial disruption, forced land loss, and the emergence of a modern tribal nation navigating economic development, infrastructure needs, and cultural revitalization in the twenty-first century.

The Tribe’s origins, land base, encounters with colonial powers, the formation of its modern government, and its current priorities in areas such as energy, water, health, language, and economic self-determination.

Homeland and Geography

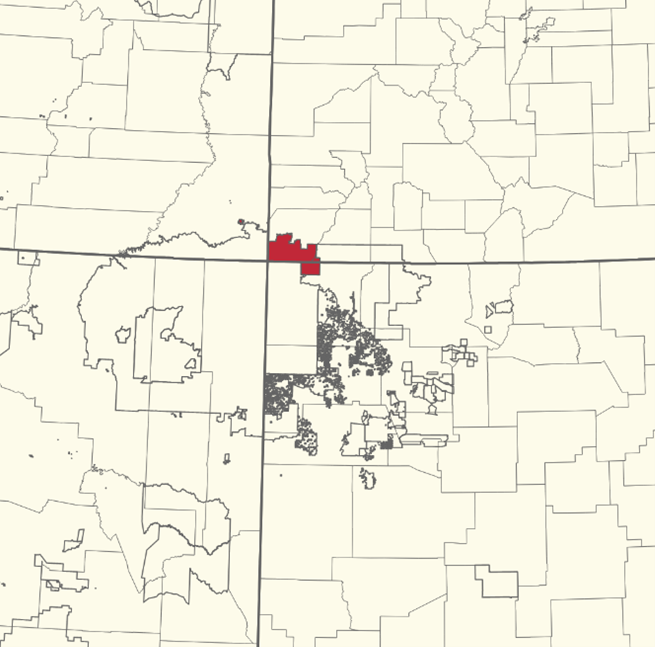

The homeland of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe lies in the Four Corners region, where Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona meet. The Tribe’s reservation lands are primarily located in Montezuma and La Plata Counties in Colorado and San Juan County in New Mexico, with additional lands associated with the Tribe in Utah, including the White Mesa community.

The Tribe commonly describes the reservation as encompassing approximately 553,000 acres, though published acreage figures vary depending on whether calculations include trust land only, fee land, satellite parcels, or lands held across state lines. These discrepancies are common in Native Indian Country and reflect the complex legal geography created by federal Indian policy over more than a century.

Dominating the Montezuma Valley is Ute Mountain, a volcanic laccolith rising abruptly from the surrounding plateau. From a distance, its silhouette resembles a sleeping figure laid across the land, a landmark that has become both a cultural symbol and a geographic anchor for the Tribe.

The mountain is not merely scenic; it is a place of meaning, story, and identity. The broader region is semi-arid, with cold winters, hot summers, and limited water resources. Agriculture historically depended on careful timing, mobility, and deep ecological knowledge. These environmental realities continue to shape life on the reservation today, influencing infrastructure planning, water policy, housing development, and economic strategy.

Deep indigenous history before European contact

Human history in southwest Colorado extends back thousands of years. Archaeological evidence documents long-term Indigenous presence, including hunting and gathering traditions, trade routes, and later the emergence of complex agricultural societies.

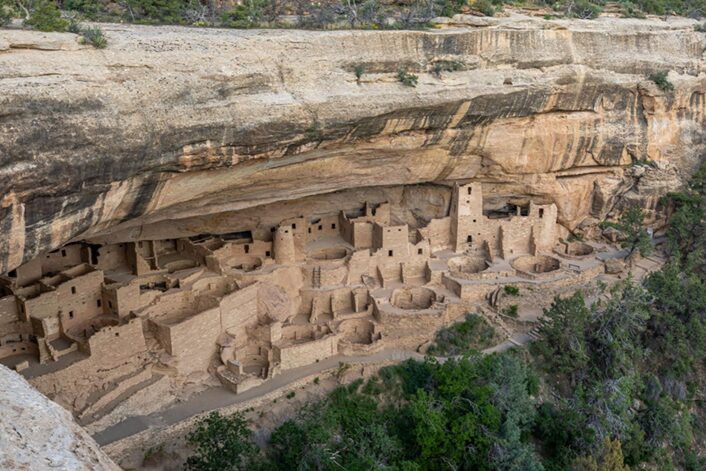

The Four Corners region is especially well known for its Ancestral Pueblo (Ancestral Puebloan) sites – multi-story stone dwellings, cliff alcoves, kivas, and extensive road networks. Many of the most famous examples lie within Mesa Verde National Park, which borders Ute Mountain Ute lands.

Equally significant, though less widely known, are the archaeological and cultural sites preserved within Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Park. Unlike national parks managed by federal agencies, the Tribal Park is owned and interpreted by the Tribe itself. Access is guided, emphasizing cultural respect, stewardship, and Indigenous perspectives on history.

The Ute people’s own history in the region reflects mobility rather than permanent stone villages. Ute lifeways emphasized seasonal movement, hunting, gathering, and trade across wide territories that included mountains, basins, and plateaus. This flexibility allowed Ute bands to adapt to climatic variation and shifting resource availability.

Importantly, Ute history does not “begin” with European contact. It exists within a deep Indigenous continuum that predates colonial boundaries and modern state lines. The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe today understands itself as a successor not only to historic Ute bands but also as a steward of a landscape shaped by many Indigenous peoples over millennia.

Spanish and Mexican periods: Horses, trade and change

Spanish exploration and colonization in the American Southwest introduced profound changes long before sustained U.S. presence. Through trade networks extending north from New Mexico, Indigenous peoples encountered European goods, animals, and diseases.

Among the most transformative introductions was the horse. By the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, horses had spread widely among Indigenous nations of the interior West. For the Ute, horses revolutionized mobility, hunting efficiency, and regional influence. Travel distances expanded dramatically, trade networks intensified, and new forms of diplomacy and conflict emerged.

During the Spanish and later Mexican periods, the Ute engaged in trade, alliance, and occasional conflict with colonial settlements and neighboring tribes. These relationships were fluid rather than fixed. Power dynamics shifted in response to access to horses, firearms, and trade goods, as well as epidemics that altered population patterns across the region.

Although Spanish and Mexican authorities claimed vast territories on maps, their actual control over Ute lands was limited. Ute bands remained politically autonomous, exercising their own authority over travel, trade, and resource use. This autonomy would be challenged far more aggressively after the United States acquired the region in the mid-nineteenth century.

U.S. Expansion and the loss of Ute lands in Colorado

The incorporation of Colorado into the United States marked a turning point for the Ute people. Discovery of precious metals, rapid settlement, and federal territorial ambitions placed intense pressure on Indigenous landholdings.

Through a series of treaties and agreements in the nineteenth century, Ute bands were compelled to cede large portions of their ancestral territory. One of the most consequential for southwest Colorado was the Brunot Agreement of 1873.

Under this agreement, the Ute relinquished approximately four million acres of land in the San Juan Mountains, opening the region to mining development. The agreement included language reserving certain hunting rights, but in practice the influx of miners and settlers rapidly transformed the landscape and marginalized Indigenous land use.

The Brunot Agreement exemplifies a broader pattern: treaties framed as mutual agreements but negotiated under conditions of coercion and imbalance. For the Ute, land loss was not merely territoriality, it disrupted seasonal movements, food systems, spiritual connections, and political autonomy.

By the late nineteenth century, most Ute bands had been forced onto reservations, often far smaller than their original homelands. In Colorado, this process culminated in the division of Ute peoples into separate tribal entities, each with distinct reservation lands and political trajectories.

Formation of the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation and Tribal Government

The Ute Mountain Ute Reservation emerged as part of this reorganization. Over time, the Weeminuche band became federally recognized as the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, with a land base centered in southwest Colorado and extending into New Mexico and Utah.

In 1940, during the era of the Indian Reorganization Act, the Tribe adopted a written constitution and bylaws. This document established a modern system of tribal governance recognized by the federal government, while coexisting with traditional forms of authority and community leadership.

Today, the Tribe is governed by an elected Tribal Council, with a Chairman elected by popular vote. The Council oversees legislation, economic development, intergovernmental relations, and administration of tribal programs. The current Chairman Selwyn Whiteskunk understands and supports the development of new industry developments that will have a direct, long term beefit to the Tribe.

Tribal government operations are funded through a combination of:

- Revenue from tribally owned enterprises, including oil and gas developments

- Federal contracts and compacts

- Grants and program funding

This hybrid funding model is common across Indian Country and reflects both the persistence of federal trust responsibilities and the Tribe’s efforts to build independent revenue streams.

Economic development in the modern era

Economic development is one of the most visible expressions of modern tribal sovereignty. For the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, this has taken multiple forms.

One major enterprise is the Ute Mountain Casino Hotel, which provides employment, revenue for tribal government, and a regional destination for visitors. Like gaming enterprises across Indian Country, it serves as a tool for funding public services rather than an end in itself.

Tourism tied to cultural heritage, including the Tribal Park, offers another revenue stream while reinforcing Tribal control over interpretation and land use.

Dating back to the 1920’s oil and gas exploration and development has been a consistent source of revenue for the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe through royalties and severance taxes.

In recent years, the Tribe has also pursued renewable energy development, including community-scale solar installations and proposals for large-scale solar projects. These initiatives reflect broader trends in Indian Country toward energy sovereignty, climate resilience, and economic diversification.

Energy development

Untapped Resource Potential

The Ute Mountain Ute Reservation sits across two major petroleum provinces: the Paradox Basin (NW part) and the San Juan Basin (SE part). In plain terms: the Tribe’s land overlies the same rock packages that host major Four Corners oil and gas fields – especially Pennsylvanian Paradox / Ismay carbonates (Paradox Basin) and Cretaceous sandstones like the Dakota and Gallup (San Juan Basin).

In addition, the Mississippian aged Helium resources while potentially extensive, remain largely unexploited.

A short timeline of development on/near their land:

- Early gas discoveries (1920s): found gas, but no market

A Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) report that Ute Dome (gas in the Dakota Sandstone) was discovered in 1921, and Barker Dome (gas in the Dakota) in 1924—but the early wells often had no pipeline/market outlets, so activity was limited for years. - Early shallow oil (late 1920s): small production, spotty records

The same BIA report describes the Mancos River oilfield as discovered in 1927 from shallow oil in the Mancos Shale interval, with a modest early drilling burst and later intermittent activity. - Post–World War II: deeper targets and real development (1940s–1950s)

After WWII, as regional pipeline infrastructure and markets improved, deeper Pennsylvanian objectives became more attractive. For example, Barker Dome saw a successful Pennsylvanian completion in 1945, after the earlier 1924 discovery had been plugged due to lack of market.

This era is also when the wider Four Corners “engine” (pipelines, refineries, demand) really began pulling the region into sustained oil and gas development. - Major reservation-era oil development (1950s–1970s): Gallup/Dakota fields and many wells

The BIA report records several oil fields within the reservation footprint (including on the New Mexico portion of the reservation) and gives dates and early production stats. Examples include:

Verde-Gallup field discovered 1955; by end of 1974, nearly 200 wells had been drilled in the field area, with millions of barrels cumulative production reported.

Horseshoe-Gallup field discovered 1957; the report describes dozens of wells on the reservation and pipeline outlets.

A notable pattern in the Colorado portion is smaller, shallow Gallup-sand lenses (e.g., Aztec Wash, Chipeta) and scattered production.

This is why a local journalist could accurately summarize that the Tribe has been “in the oil and gas business for over 70 years.” - Modern era: “plays” and leasing opportunities mapped

BIA’s Division of Energy and Mineral Development (DEMD) produced an “Oil and Gas Plays” atlas document specifically for the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation, framing the reservation in terms of conventional play types and analog fields in/near the reservation.

This matters because it’s the technical backbone tribes and operators often use for leasing strategy: what formations, what traps, what historical analogs, what risks.

How development typically happens on Tribal trust lands

Most of the reservation surface/minerals are tribal lands held in trust by the U.S. government, as described in BIA materials. In practice, oil & gas activity tends to involve:

- A negotiated lease/terms approved through tribal processes, and,

- A federal oversight/approval process that attach to trust lands (with the Tribe retaining sovereignty and setting conditions).

- The Tribe itself describes an Energy Program that seeks development while “minding tribal culture and sovereignty.”

Where helium fits into the story

Historically helium in the Four Corners was often tied to CO₂ domes and some natural gas systems. In the broader region, helium can occur:

- as a minor component in natural gas, and/or

- in some CO₂-dominant reservoirs (natural CO₂ fields).

A key nearby example is McElmo Dome in southwest Colorado, famous primarily as a natural CO₂ source for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) via pipelines (like the Cortez Pipeline system). A federal helium resource assessment notes McElmo Dome contains a very large volume of gas but only about 0.07% helium, making helium extraction historically considered unlikely even though total helium in place can still be large due to the field’s size.

Recent helium exploration on Ute Mountain Ute land (2024)

A new leasing chapter

In late 2024, Quantum Helium received approval from the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe to lease 4,320 acres to explore helium in Colorado, designated the Coyote Wash IMDA. In addition, Quantum Helium acquired a large producing oil lease, with helium potential from Seeley Oil Company.

Helium has become a distinct target (separate from classic oil/gas development), reflecting modern helium markets and the renewed interest in domestic helium sources.

In recent years the Tribe has publicly discussing that oil/gas revenues decline over time and the importance of diversified enterprises (including shifts toward solar and Helium), consistent with DOE project documentation.

Helium is now a visible new frontier via exploration leasing activity. Helium production can be extremely valuable to the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and has the potential to grow the revenue the tribe receives to historic levels.

If helium is produced and sold, the Tribe typically earns a royalty as a percentage of the value of production, in addition to lease bonuses, revenue is derived from taxes and special contributions toward community development.

Those are meaningful because they’re low-risk revenue (you get paid even if drilling fails), though usually much smaller than production royalties.

If Quantum Helium is successful in developing Helium in their Sagebrush and Coyote Was exploration areas the value to Tribe can be widespread:

- Higher royalty base than methane-only projects (helium value uplift)

- Job creation (field ops, trucking, maintenance, environmental monitoring)

- Service contracts for tribally owned/tribal-member businesses

- Tax/fee pathways (depending on tribal law and agreements)

- Longer-lived, steadier production

Summary

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe is a federally recognized Indigenous nation whose presence in the Four Corners region of southwest Colorado, southeast Utah, and northwest New Mexico extends back many centuries, long before modern borders existed.

As part of the Ute people, the Tribe’s ancestors lived across a vast territory through seasonal movement, hunting, trade, and deep knowledge of the land, with Ute Mountain serving as a cultural and geographic anchor.

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe remains a sovereign government today, exercising authority over its lands, preserving language and culture, and managing economic, environmental, and community development initiatives that reflect both continuity with the past and adaptation to the modern world.

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe has a nearly century-long history of oil and gas resource development on it’s lands and substantial experience managing mineral resources under tribal trust and federal oversight.

Helium – particularly at the Sagebrush area – represents a new category of opportunity: a high-value mineral tied to global medical and technology supply chains rather than traditional energy markets. If commercial production is achieved, helium could provide diversified, long-term revenue to support priorities such as water infrastructure, housing, healthcare, language preservation, and government services.

The value to the Tribe will ultimately depend on exploration and development success, infrastructure access, and environmental protections, making strong governance, bonding, audit rights, and tribal employment provisions essential to ensuring the resource strengthens sovereignty rather than creating future liabilities.

Unlike oil and gas, helium is rare and strategically important element, which is why it has drawn new interest. If development proves successful, helium production could help fund community needs and reduce reliance on a single industry.

At the same time, the Tribe is approaching this carefully balancing economic opportunity with protection of land, water, and long-term community well-being. Exploration does not guarantee production, and decisions are being guided by both economic analysis and tribal values.